Menopause - Country-specific information of Indonesia

Ali Baziad (1) and Dr Cipto Mangunkusumo (2)

(1) Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Indonesia, Jakarta

(2) General Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia

Statistics

The number of women aged 40-65 according to the population data form the Ministry of Health 1996:

1971: 9,577,726

1980: 12,944,825

1990: 16,128,977

It is projected that by the year 2000 the number of women aged 40-65 will be approximately 21,891,200.

The population composition for the period of 1980 to 2020 shows a marked dif-ference in the number of children under 5 years compared with elderly people. The number of children under 5 years will decrease from 21,190,672 (14.4%) in 1980 to 17,595,966 (6.9%) by 2020. By contrast, the number of elderly people will increase from 7,998,543 (5.5%) in 1980 to 29,021,128 (11.4%) by 2020 (Table II).

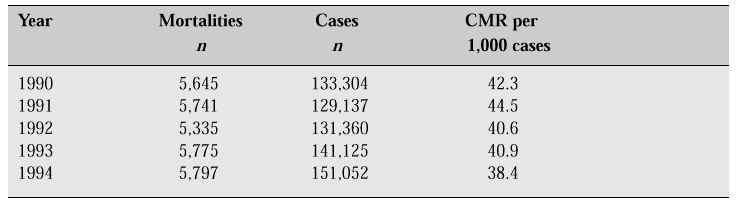

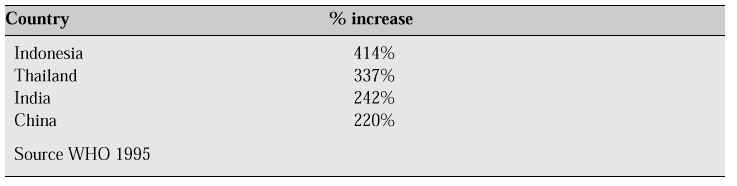

Table I: Projection of the increase in the elderly population by 2050 compared with 1990.

Table II: Population development of elderly people and children under 5 (0-4 years) in Indonesia from 1980 to 2020

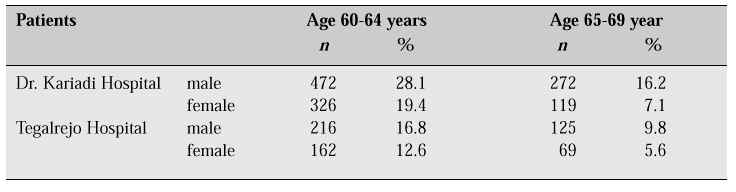

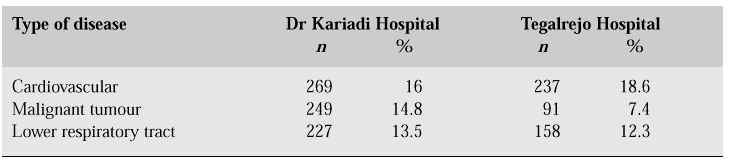

Indonesia’s success in improving the welfare of its people within almost three decades has resulted in an increased life expectancy. In 1980, female life expectancy was 50.9 years (males 54.0 years); in 1990 these figures were 62.7 and 59.1 years, respectively, and it is estimated that by the year 2000 they will have increased to 70 and 60 years, respectively. As a consequence of the increased number of elderly women, various health problems will be encountered more frequently. In the elderly population, cardiovascular diseases generally came in first place, followed by musculoskeletal disorders. The study undertaken at St. Elizabeth Hospital, Semarang (Central Java) by Budhidarmojo in 1087 elderly subjects suggests that people >60 years suffer mostly cardiovascular, infectious and cerebrovascular diseases. In 1992, a study was performed at two hospitals, i.e. Dr. Kariadi Hospital (Semarang) and Tegalrejo Hospital. Dr. Kariadi Hospital is a government hospital serving as referral hospital, while Tegalrejo Hospital is a private hospital, and patients admitted at this hospital are of the upper socioeconomic strata. The disease most commonly suffered by both males and females at both hospitals was cardiovascular disease.

Table III: Elderly patients treated

Table IV: Diagnoses in elderly patients

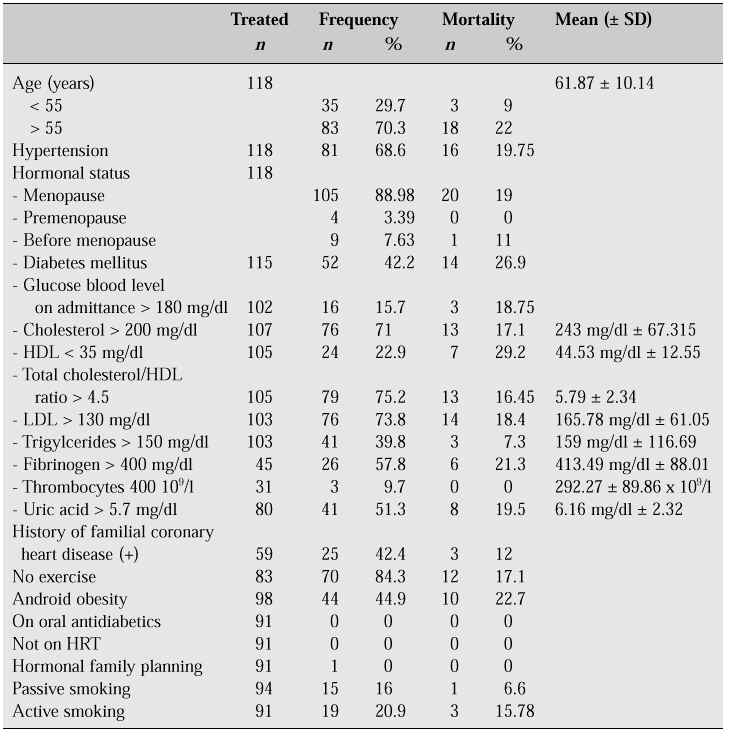

The therapeutic modes generally applied at both hospitals are medical, pharmacologic, and operative therapy as well as physiotherapy. The most frequently occurring cause of mortality is cardiac arrest. Table V contains an overview of the characteristics of 118 female patients with acute myocardial infarction treated at the Harapan Kita National Cardiac Center from January 1, 1993 to May 31, 1995.

Table V: Risk factors of coronary heart disease (female patients)

In 1980, the average age of menopausal women in Jakarta was 44-45 years, while in 1990 it was 50 years. The women studied were those of the upper socioeconomic strata. Types and frequency of complaints were: hot flushes 93.4%; sleep disorders 31%; palpitations 62%; bone pain, 57%; libido disorders, dysuria, painful sexual intercourse 58%; night sweats 67%.

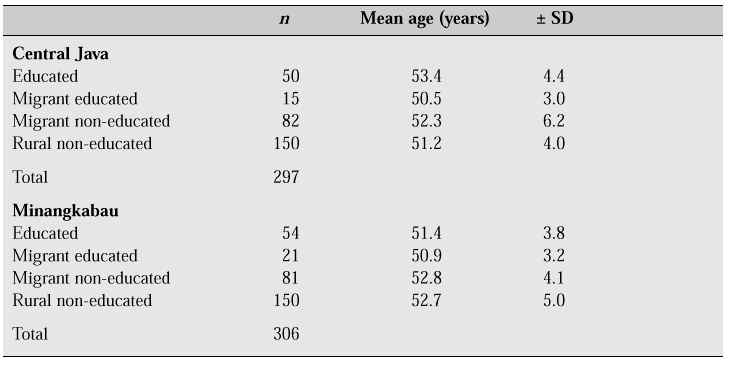

In 1985-1986, a study was conducted in Java and West Sumatra (Minangkabau). The respondents in this study totaled 603 postmenopausal women. Of these, 297 were Central-Javanese living in the urban and rural area (Table VI).

Table VI: Education level and age of respondents

The socioeconomic classes of these subjects were divided into upper, middle and lower. The religious affiliation of both Javanese and Minangkabau was stated as Moslem for most of the subjects in this study.

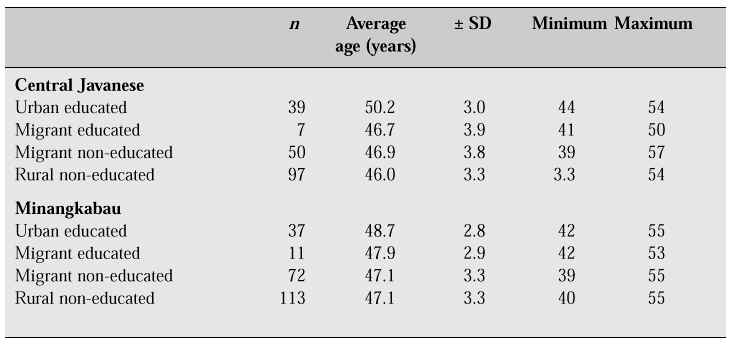

The mean age at menopause was 50.2 years (Table VII) for educated Central-Javanese women. This is approximately the mean age of menopause in the USA and Europe.

Table VII: Mean age at menopause in relation to education

For educated Minangkabau women, the mean age at menopause was 48.7 years. The educated Central-Javanese women were from the upper socioeconomic class. In contrast, the urbanized Minangkabau women lived in a large town, Padang, which is not as developed as the capital of Jakarta.

Climacteric complaints were treated only symptomatically. Only a small number of patients presented for consultation with a physician. Special guidance for meno-pausal women did not exist at both hospitals and health centres, and those admitted for treatment were generally given tranquilizers (40%).

Those not consulting a physician treated themselves by means of traditional medicines such as native herbal tea. The first menopausal clinic in Indonesia was established in Jakarta in 1990. This clinic was part of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Indonesia. In 1996, the first private menopausal clinic was established in Jakarta as part of the private collaboration between Austria and Indonesia. By 1992, there were only three hospitals providing special services for the elderly, one in Jakarta and two in Semarang.

Although by now menopausal clinics are available, the number of women presenting for treatment is still very limited. Indonesian women, either in rural or in urban areas, consider menopausal complaints as something normal, although they may be quite disturbing. Complaints like bone pain are considered as rheumatics, and they are treated by means of rheumatic medications obtained without prescription. Sleep disorders, depression, tension, and irritability are treated by means of tranquilizers and sleeping pills. In addition, a large number of physicians, either specialists or general practitioners, have not fully understood HRT. For example, of 70 women with com-plaints of dyspareunia, only 29% consulted a physician – and their treatment consisted only of sedation.

Through information in mass media and seminars, physicians come to understand that HRT has more positive than negative aspects. However, HRT use in Indonesia is still very limited. Fear of breast cancer is the leading cause: there are a large number of physicians in Indonesia who still regard HRT as the cause of breast cancer.

As we know, HRT is a long-term process and its efficacy will be evident only after several months. This situation frequently makes the patient impatient and tired of tak-ing the medication. The patient wants to be relieved of her complaints within one or two days.

Many requirements have to be met and an examination must be done prior to HRT administration; besides, the patient has to undergo frequent controls during HRT use. The medication is relatively expensive and generally the patient has to pay by herself. Health insurance is voluntary in nature.

Since 85% of the Indonesians is Moslem, any bleeding occurring during HRT use is considered as a nuisance to prayer activities. As a matter of fact, bleeding of this sort is different from the bleeding caused by menstruation. During menstruation prayer is not justifiable, while bleeding caused by HRT use can be justified while performing prayer.

There are many physicians without an adequate understanding of HRT, and they consider the hormones contained in HRT similar to those in oral contraceptives. If the bleeding occurs during the use of HRT, the patient is usually advised to undergo curettage. This intervention is not very favourable with patients, to the extent that they will not willingly come for further treatment.

Because the number of menopausal women is steadily increasing and most of them are from the lower socioeconomic strata, the Government of Indonesia has initiated a number of activities, such as:

1. Provision of services through health centres and primary health services, such as general practitioners and integrated service stations (posyandu).

2. Establishment of menopausal clinics at each hospital, or units of geriatric service.

3. Establishment of private menopausal clinics in big cities.

4. Midwifery regulations of menopause.

5. Enhancement of the participation of family physicians (general physician plus).

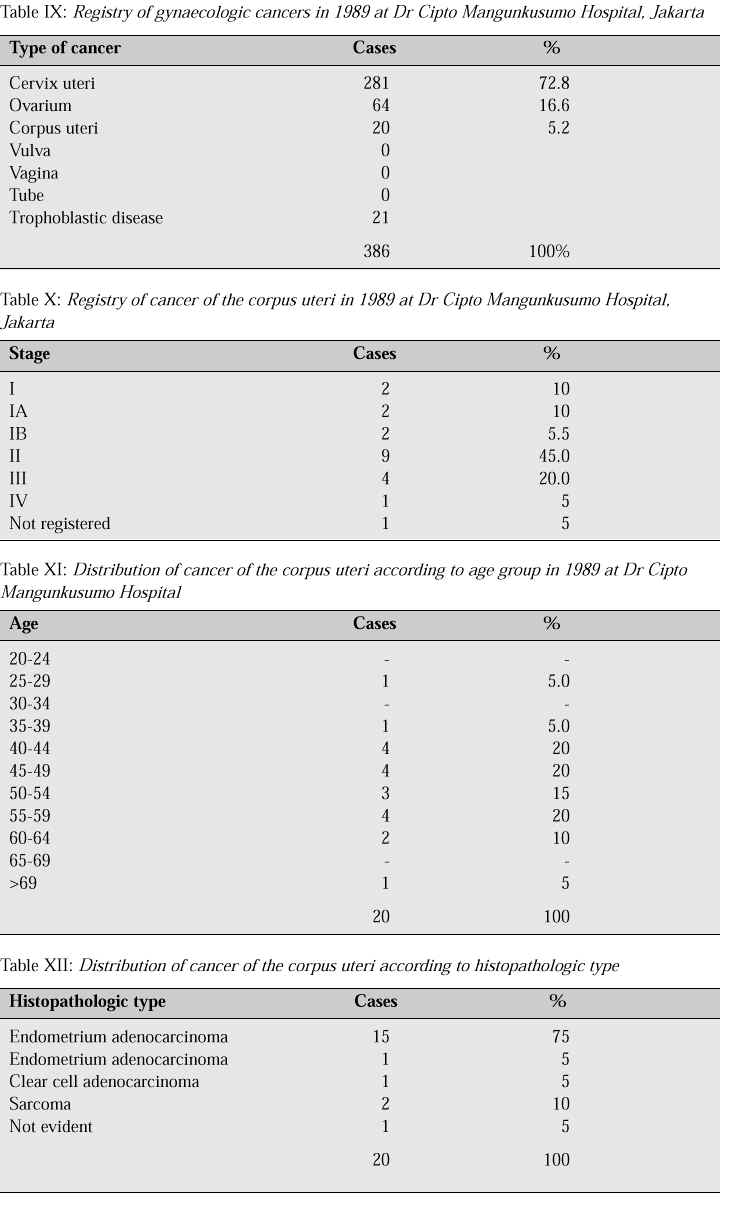

Breast cancer remains an important problem in developing countries such as Indonesia. The data collected from 13 pathology laboratories spread all over Indonesia by the National Center for Pathology show that breast cancer ranks as the second most common cancer among females, with a relative frequency of 18.03% (ASCAR = aged-standardized cancer ratio 17.84%) in 1988 and 18.44% (ASCAR 17.46%) in 1989.

The annual incidence of breast cancer in Japan has been reported to be lower (12.1–16.6 per 100,000 females) than in America (71.7 per 100,000 females). In Indonesia, the incidence rate was 18.6 per 100,000 females.

The majority of women with diagnosed and treated breast cancer in the general hospital show up rather late, and they have a very low probability to be cured. Most of them are diagnosed at a late stage, while those who are diagnosed at an early stage prefer to go to traditional healers. When at last they are referred back to the hospital, they usually are in a late stage of the disease. Most women with breast cancer came from a middle to lower socioeconomic level.

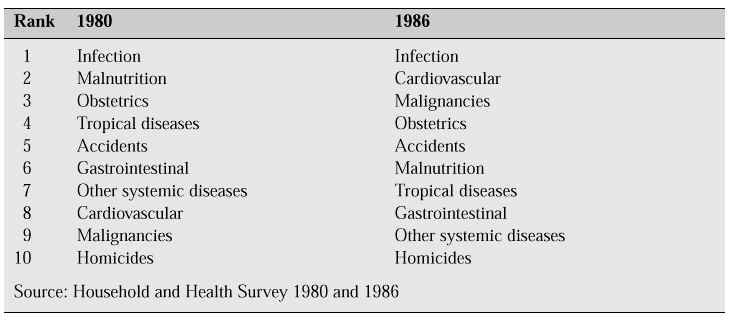

Table VIII: The 10 most prevalent causes of mortality

Breast cancer has mostly been found in the age groups under 35 years and between 40-44 years. The majority (87%) of the cases were in an advanced stage (IIIA, IIIB).

Epidemiological analysis of risk factors for breast cancer in Indonesian females

This study found that the most prominent risk factors were induced by menopause and short-term breastfeeding or lactation, i.e. less than 4 months (RR=5.59 and 5.44, respectively). The risk of breast cancer was three times higher in underweight patients, closely linked genetic traits and fatty diet (RR: 2.2, 2.85 and 2.63, respectively). A relationship between hormonal contraceptives and risk of breast cancer has not been shown in this study. Fatty food was found as one of the important risk factors. As for demographic origin, urban dwellers were at increased risk (RR: 2.22; 95% CI = 1.63-3.02).

Epidemiological risk factors for breast cancer related to menopausal status

To clarify the risk factors for breast cancer in premenopausal and postmenopausal women, a hospital-based case control study was conducted in Indonesia. Three hun-dred women with breast cancer were interviewed and 600 controls were selected, matched for age and socioeconomic class. The following significant findings were revealed: for premenopausal breast cancer, an increased risk was detected in women with breast trauma (adjusted RR: 2.62; 95% CI: 1.09-6.31); OC use 4.96 (1.51-16.4); milk consumption 1.81 (1.01-3.25) vs no milk consumption; fresh fruit 3-4 times/week 2.42 (1.16-5.05), vs less than once/week. A decreased risk was detected in women with daily consumption of cooked vegetables (0.34; 0.15-0.77) vs not-daily consumption. For postmenopausal breast cancer, an increased risk was found in women with age at menarche of ³15 years (2.25; 1.35-3.76); regular menstruation after age 30 (4.61; 2.44-8.67); daily milk consumption (5.84; 2.92-11.66) vs no milk consumption. A decreased risk was found in postmenopausal women who were divorced or widowed (0.33; 0.18-0.59), and in women with many livebirths and many occasions for breastfeeding (0.32; 0.13-0.76).

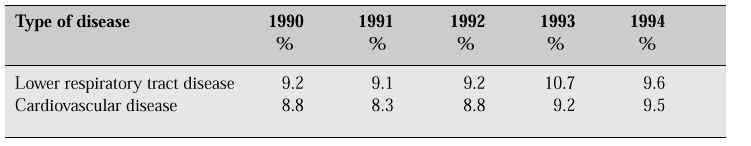

Table XIII: Mortality pattern of diseases at hospitals in Indonesia (1990-1994)

Maternal mortality was estimated to be 450/100,000 livebirths. The maternal mortal-ity rate in Indonesia is still very high compared with other Southeast Asian countries, and even higher than the average of developing countries. According to the Assistant Minister of Women’s Affairs; reduction of the maternal mortality rate in Indonesia is being jeopardized primarily by cultural tradition, socioeconomic aspects, gender dis-loyalty, inadequate education, services, and health facilities. However, if these pro-blems are put together they can be separated into sociocultural and economic aspects, services, health facilities or clinical management. The survey shows that more than 80% of maternal mortality can be attributed to the classic trias: bleeding (40-60%), birth canal infection (20-30%), and gestosis (20-30%).

Generally, this classic trias can be improved upon by adhering to three admoni-tions: 1) do not be late in deciding to refer to the nearest health facilities; 2) do not be late to reach the health centre or hospital; 3) if the patient has arrived at the hospital, do not be late in supplying appropriate management.

The inadequacy of health service coverage is, among others, caused by geograph-ic conditions, population distribution, inadequate health facilities, and the quantity and quality of health personnel. It turned out that only 30-40% of the first referral facilities, i.e. district hospitals, had obstetricians and gynaecologists, on their staff. Furthermore, even in hospitals where medical specialists are available, it is still uncertain whether they are able to conduct comprehensive obstetric emergency services on a full-time basis. On the other hand, because of geographic obstacles, distances between a health centre and the hospital can hardly be bridged within 2 hours.

Referral procedures themselves have not been optimized, and some cases of maternal mortality are due to late arrival at the referral centre. Many deliveries take place at home and are being assisted by traditional birth attendants or midwifes. These women are at the frontline of obstetric services. Most cases of hospital maternal and perinatal mortality occur in women having been referred from home. Many women prefer delivery at home because they feel closer to their family and neighbours. In addition, room is always available, and cross-infections may be prevented at home. However, the most important factor for home delivery is that it is less expensive. Nevertheless, there are also some disadvantages, such as assistance by traditional birth attendants or midwifes, usually consisting of just one person. In addition, sanitation, facilities, equipment and clean water are inadequate, and if a referral is wanted, transportation and assistance will be necessary during travel. The WHO has esti-mated that 500,000 pregnant women throughout the world become victims of repro-duction each year (Source: Abdullah Cholil, MPH, Assistant Minister 1 for Women’s Affairs and Jusuf Hanafiah, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine, North Sumatra University, 1997: March 19, page 15).

Based on a report from various regions over a period of 10 years (1987-1997), a very high incidence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) was found in three provinces out of 20, i.e. Jakarta, Riau, and Irian Jaya. The number of HIV/AIDS cases currently reaches more than 169,000. Distribution according to age shows that most patients belong to the reproductive age group (15-49 years), encompassing 80% of all cases.

The magnitude of the number of HIV/AIDS patients in the reproductive age group is attributed to the increased industrialization in Indonesia which has resulted in the development of a great number of industrial centers. Industrial centers pull migrant groups from rural areas to cities as labour force. In the cities the migrants were like-ly to find a life with less restrictions, such that the desire to maintain the old social norms disappeared. An overwhelming exposure to tempting mass media of various kinds as well as loose social norms have created an environment vulnerable to the risks of sexual transmitted diseases.

Health level

1. Mortality rate

1.1. Infant hospital mortality rate

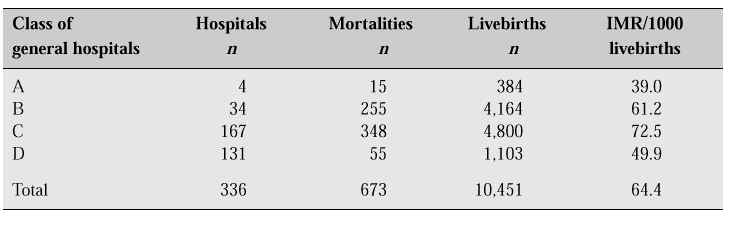

Table 2.I shows that from 1990 to 1994 infant mortality rate at the hospitals decreased from 64.9 per 1 000 livebirths in 1990 to 49.1 per 1,000 livebirths in 1994. Compared with other studies performed in the community, such as the 1986 Household and Health Survey which found an IMR of 87 per 1,000 livebirths, infant mortality at hospitals is far lower. The infant mortality rate at general hospitals of class A, B, an D is 39-61 per 1 000 livebirths, while general hospitals of class C have a higher rate of infant mortality. This is because the general hospital of class C serve as referral hospitals in their area,and as such patients admitted usually are in a critical condition. Compared with IMR in all hospitals (49.1), general hospitals of the Regional Government, Department of Health, have a higher mortality rate, i.e. 64.4. However, this finding does not suggest that these hospitals are poorer in their services; the general hospitals of class A, B, C & D serve all levels of the community, and usually the patients referred to these hospitals are in a critical condition.

Table 2.I: Infant mortality rate (IMR) at Indonesian hospitals (1990-1994)

50.5% of infant mortalities (340 of 673 mortalities) at the general hospitals of class A, B, C & D are caused by diseases originating in the perinatal period. At a national level, 483 of 913 infant mortalities (52.9%) are caused by diseases originat-ing in the perinatal period. 43.7% of diseases originating in the perinatal period are caused by premature and immature birth, and 3.9% by tetanus neonatorum. This find-ing suggests that 47.6% of perinatal mortalities are largely determined by maternal conditions before delivery. Premature and immature births are a disorder attributed to a short period of pregnancy and unspecified low birthweight.

Table 2.II: Infant mortality rate at general hospitals of class A,B,C,&D (1994)

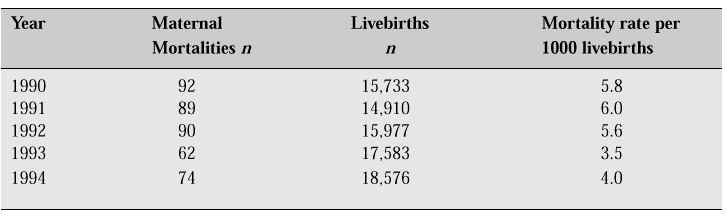

1.2 Hospital maternal mortality rate in Indonesia

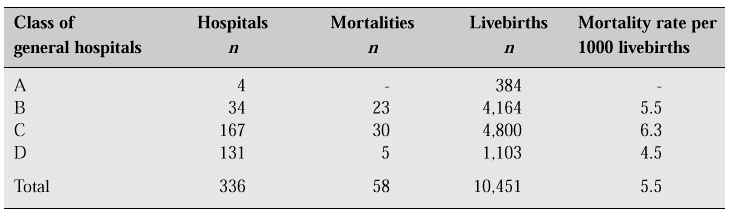

Table 2.III shows that from 1990 to 1994, maternal mortality at the hospitals experi-enced a decrease, compared with maternal mortality rate at a national level, as sug-gested by the 1986 Household and Health Survey i.e. 4.5 mortalities per 1000 live-births. There are a number of determining factors, including an effectieve referral sys-tem, and whether patients referred to the hospital by a lower unit have been managed properly. Other factors affecting maternal mortality are, among others, the education-al level of the mother, occupation, birth assistance, equipment/blood transfusion facilities and transportation. Table 2.IV: Maternal mortality rate at general hospitals of class A, B, C, & D (1994)

Table 2.III: Maternal mortality rate in Indonesia

Table 2.IV: Maternal mortality rate at general hospitals of class A, B, C, & D (1994)

Maternal mortality rate at general hospitals of class A, B, C & D managed by the Regional Government (Pemda) was 5.6 per 1000 livebirths. This figure is much higher than the maternal mortality rate at national level in 1994, i.e. only 3.5 per 1000 live-births (see Table 2.IV).

As for class of hospitals, it turns out that general hospitals of class C have a high-er mortality rate, i.e. 6.2 per 1000 livebirths. This is because hospitals of this type provide services and management for referrals which have not been dealt with properly.

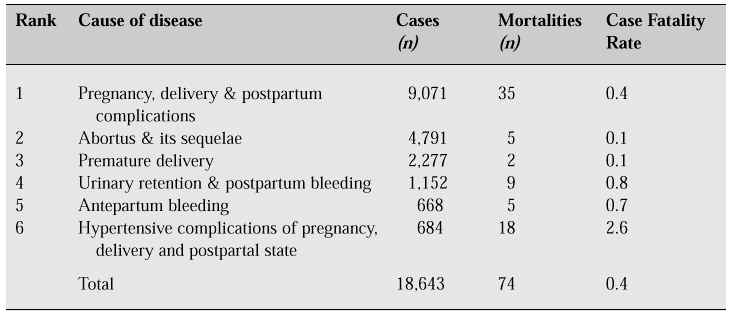

Viewed from the cause of disease, it is evident that obstetric cases are largely found in complications of pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum, i.e. 48.7% (9071 out of 18,643 cases), and that mortalities mostly occur in the same group, i.e. 47.3% (35 of 74 mortalities) (see Table 2.V).

Table 2.V: Distribution of obstetric patients according to cause of disease

Hypertensive complications of pregnancy, delivery, and postpartal state are the most frequent cause of death with a CFR (case fatality rate) of 2.8%.

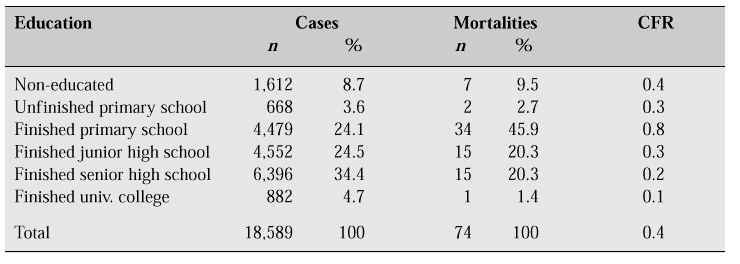

Of 18,589 cases classified for education, most cases (27.8%) had a primary school level. Looking at the number of mortalities, 36 of 74 (48.6%) occurred in the group with primary school education.

It is evident that mortality is overrepresented in the group with educational level of primary school downwards (cases 24.2 + 3.6 + 8.7% = 36.5%; mortality 45.9 + 2.7 + 9.5% = 58.1%).

Table 2.VI: Distribution of obstetric patients according to education (1994)

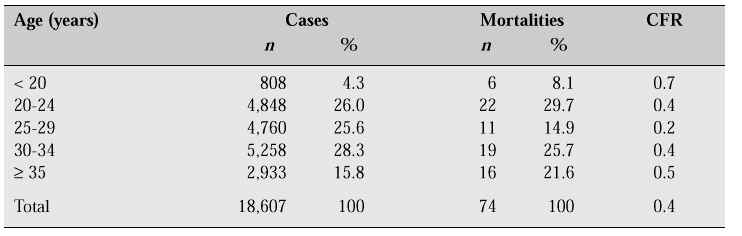

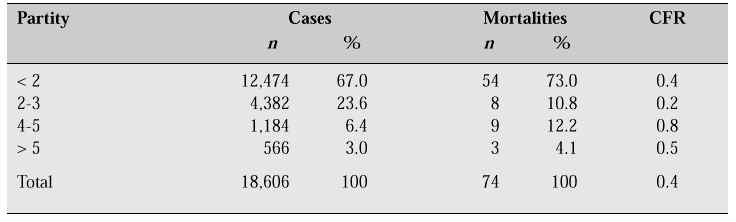

Mortality at ages 20-24 is higher than that at ages 30-34; CFR, however, is the same (0.4), while the highest CFR is found at ages under 20 years. This finding shows that delivery is less safe under 20 years of age. Women with parity 4-5 seem to run the highest risk of mortality.

Table 2.VII: Age distribution of obstetric patients (1994)

Table 2.VIII: Distribution of obstetric patients according to parity (1994)

1.3. Crude mortality rate (CMR)

Table 2.IX shows that hospital CMR does not change significantly from year to year. In contrast with hospital CMR, the nationwide crude mortality rate tends to decrease from year to year, as shown by the census of 1980 (CMR 12.6) and by the Population Survey between Censuses (Supas) of 1985 (CMR 9.1).

Table 2.IX: Hospital crude mortality rate (1990-1994)